|

Alan Sorrell Archaeological Work |

|

It was in 1936, according to his own account, that archaeology as such first stirred Alan Sorrell’s interest. He was staying in Leicester by chance while Dr Kathleen Kenyon’s excavations of the Roman forum were in progress. This was a busy scene which he recorded in a drawing. The drawing was shown to Sir Bruce Ingram, editor of The Illustrated London News, who proposed to publish it alongside a ‘restoration’ of the forum from the same viewpoint, upon which artist and archaeologist should collaborate. The drawings duly appeared in February 1937. The immediate result was a request from Dr (and later Sir) Mortimer Wheeler for a reconstruction drawing of the Roman Assault on the eastern entrance of Maiden Castle, which would incorporate the evidence of his recent and widely publicised excavations: this appeared in The Illustrated London News in the following December. Sir Cyril Fox and V.E.Nash-Williams of the National Museum of Wales were also keenly enthusiastic. With them, Alan Sorrell worked in close collaboration between 1937 and 1940 on a series of archaeological reconstructions for the Museum, chiefly of Welsh sites of the Roman occupation, and for the first time, archaeology dominated his artistic output. |

|

Two of these drawings—one of Roman Caerwent, and the other of the legionary fortress at Caerleon– are panoramic views, and others are more intimate scenes, with Roman houses and other structures: all have a high eye-level. The advantage of the high viewpoint had already been explored in the Southend decorations. In these drawings, Alan Sorrell returned to the rigorous preparations that had characterised those early historical-romantic works. The ‘learning’ of each subject was made easier in this case by the labours of scientific excavation, but in the absence of historical comparisons, the imaginative leap required to bring the past to life was the greater. Roman Britain, in particular, had scarcely been treated by an artist before, and certainly not by one disciplined by reference to specific sites and archaeological fact. To be true to fact, and also imaginative and artistically true, and therefore convincing, was a considerable task. In his working methods, he naturally drew upon his experience of mural painting, and favoured a gradual approach. A visit to the chosen site was always his most important sourced of information—not only to study, with the archaeologist, the visible remains, but also to learn the rise and fall of the ground, and the character of the landscape, trying always to ‘get inside the minds of the old builders, and savour something of their problems and achievements’. Then, form maps, plans, photographs and his own sketches would grow the first scribble of the design, which developed—precisely as in the mural paintings– through a series of preliminary sketches, up to a full-sized ‘cartoon’, and thence to the final work. The ‘cartoon’ was submitted in each case to Fox and Nash-Williams, with points for elucidation written in the margin; they returned it with their answers; it was a working drawing in the fullest sense. He found this gradual approach the most convenient way of handling complex material, and was to use it for the rest of his life, broadened and simplified at last, but fundamentally unchanged. |

|

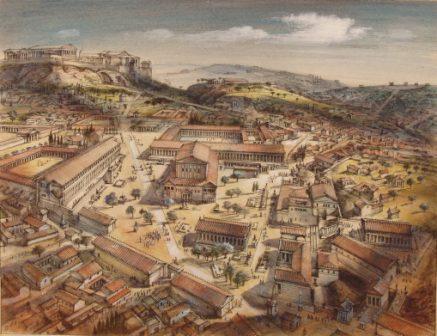

After the War, Alan Sorrell returned to his post at the Royal College of Art, but his long association with that body ended abruptly two years later in the fracas involving the dismissal of almost the entire teaching staff, following the appointment of a new principal. He now made the bold decision to live entirely by his work, and resolved to do so by developing the archaeological reconstruction. He renewed his connection with the National Museum of Wales, and The Illustrated London News, and was soon busily engaged. One of the first of these reconstructions was a fine drawing from 1949 of the Roman villa at Llantwit Major. Nash-Williams had written to him in 1938: ‘I wish you could see the Roman villa I am opening up. It is in an extraordinary state of preservation and in every way a most interesting site’ - but the War had intervened, and the excavation and reconstruction were delayed by ten years. Other reconstructions at this time were chiefly of Roman sites. A notable exception was a group of drawings—first dating from 1949– of the Viking and Prehistoric settlements at Jarlshof in the Shetland Islands, where the archaeologist was John Hamilton. Alan Sorrell work was not limited to sites in the British Isles. He contributed three large reconstructions of Knossos, Jericho and Mohenjo-daro (India) to the Festival of Britain in 1951. In 1954 he was sent by The Illustrated London News to Greece and Istambul to gather information for reconstructions at half a dozen sites—among them Mycenae, the Agora at Athens, Nestor’s palace at Pylos, and the primitive Greek settlement at Emporio on Chios—and he seized the opportunity to make many drawings. He worked in England with Professor Ian Richmond on the Carrawburgh Mithraeum on Hadrian’s Wall. He was closely involved with the London and Guildhall Museums for many years. In 1954, working with Professor Grimes, he produced drawings of the Walbrook Mithraeum, whose excavation aroused keen public interest. |

|

The Ministry of Works (later the Department of the Environment) was considering ways at this time to popularise the many ancient monuments in its care, by making them more accessible and intelligible to the general public. Travelling exhibitions had already been mounted with some success, using photographs, diagrams and text to explain aspects of the development of the medieval castle and abbey. In 1956, Hadrian’s Wall was under consideration for a venture of a similar sort. The material to had included a number of small models , but for a fuller and more adequate visual treatment , reconstruction drawings were required, and Alan Sorrell was approached to supply them. In late May, therefore, he travelled up to the Roman Wall, and spent three days visiting sites. They were: Housesteads Fort, the civil settlement outside the walls of the Fort, and the Roman supply station at Corbridge. Housesteads was visited ‘on a characteristically stormy day’, and the storm survived into the reconstruction, expressive of wilderness and isolation. Returning home to his studio, he set ot work with accustomed ease and assurance, and within two days had completed the Corbridge drawing, while the reconstruction of Housesteads occupied no more than four days apiece. A smaller drawing, of Harrow’s Scar Mile-Castle and Willowford Bridge, also belongs to this period. Soon after, the drawings were shown to the Minister, Lord Molson, who was excited by their possibilities. He agreed that this talent should be more widely employed by the Ministry, and in fact, a series of reconstructions was commissioned, beginning with drawings of three Edwardian castles in Wales, Conway, Harlech and Beaumaris, produced with the assistance of Dr Arnold Taylor. This led on, in 1957, to further drawings, of Stonehenge, Minster Lovell Hall in Oxfordshire, and the Jewel Tower at Westminster, and to official approval of the scheme in an answer given in the House of Commons: ‘The Ministry of Works are anxious to enable the general public to visualise what ancient monuments looked like in the days when they were in use. Mr Alan Sorrell has therefore been employed to carry out drawings . . .’. Thereafter, the scheme broadened rapidly, to embrace most of the popular sites in the country; each site was to have its drawing, a photograph of which would go on display, for the use of visitors. The reconstructions would not be claimed to be exact, but they would be as accurate as archaeological and historical advice could make them and they would give the visitor a much clearer idea of the significance of the ruins that lay before him, than had been possible before.

|

|

This work for the Ministry occupied him intensively for four or five years, and intermittentely for a longer period. His last twenty years until his death in 1974 were indeed the happiest and most productive of his life. With his archaeological drawings he had opened up a new field of the artist, which he continued to exploit successfully and with distinction. His commissions grew many and varied, with drawings for books, television and museums throughout the country. At the same time, he was able to turn a searching eye on the contemporary world. In 1957, for instance, when he could hardly satisfy the demand for archaeological reconstructions, he embarked on a series of drawings recording the building, at Hinkley Point in Somerset, of an atomic power station—a project which continued through five years, stage by stage, from muddy site and sandy shore, to its grand culmination in glass and concrete. Again in 1962, he travelled in Egypt and Nubia for two months, to ‘record’ in drawings the ancient temples of the Nile, under threat of destruction by the building of the new High Dam at Aswan. In both cases, he worked with a keen sense of the process of history in the making, and was pleased to assert, here also , the value of an artist’s contribution, complementing the exhaustive but nerveless mechanical recording of the camera. |

|

“Theodosian Walls, Istambul” 1954 Ink, w/c, gouache, 21” x 15” |

|

Working drawing of Caerwent, With notes showing the collaboration with the archaeologists. |

|

Stonehenge (from Prehistoric Britain) |

|

Maiden Castle(above)

The Roman Assault (below)

|

|

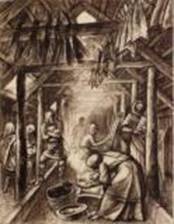

Saxon Long house |

|

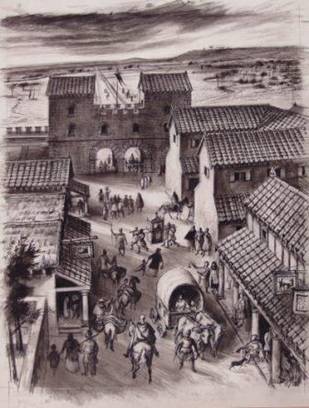

Street Scene Roman London (from Roman Britain) |

|

Athens The Agora |

|

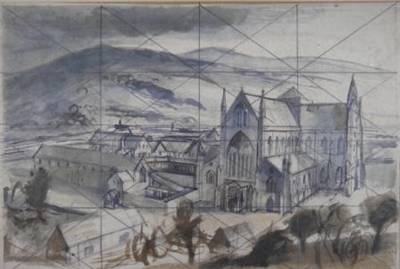

Tintern Abbey Working drawing |

|

Contact details:

Contact Julia Sorrell on: 01953 498736

e.mail: juliasorrell’at’ ukartists.com

Please replace the ‘at’ with an @, this is measure to reduce spam. We apologise for the inconvenience. |